Encrypted Provenance Repositories in Apache NiFi

Encrypted Provenance Repositories in Apache NiFi

There has been a surprising level of Twitter demand for more security-focused NiFi blogs. I’ll try to address this underserved market with a post about a new feature in Apache NiFi 1.2.0 – encrypted provenance repositories (NIFI-3388). As a mentor of mine often said, “You don’t understand something until you can teach it.” In this article, we’ll find out if I actually understand the code I wrote. First I’ll give a brief explanation of the provenance feature for anyone unfamiliar with it, describe how the existing implementations work, and introduce a new option that is sure to have people very excited (no guarantee of excited people actually offered).

What is Provenance?

Provenance is a term we use in the NiFi community with a very specific intent. The great bastion of knowledge, Wikipedia, defines it as “the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object.” Substitute “data” for “historical object”, and you’re on the right track for NiFi. A serious concern in any dataflow routing & management platform is “what happens to the data?” and “when?”. Only slightly less important is “how do we prove it?”

NiFi allows users to answer these questions by automatically recording everything that happens to your data on a very granular level. Think of “data lineage” as a family tree where each person has a Ken Burns biography – a very complete history of everything they did and how it relates to everyone else. Any event (data being created, ingested, routed, modified, tagged, viewed, exported, or deleted) is recorded, along with the time, the identity of the component that acted on it, where it was sent, what was changed, etc.

Not only does this extensive dataset allow users to query the history of their data, it enables some other powerful features as well.

Explore

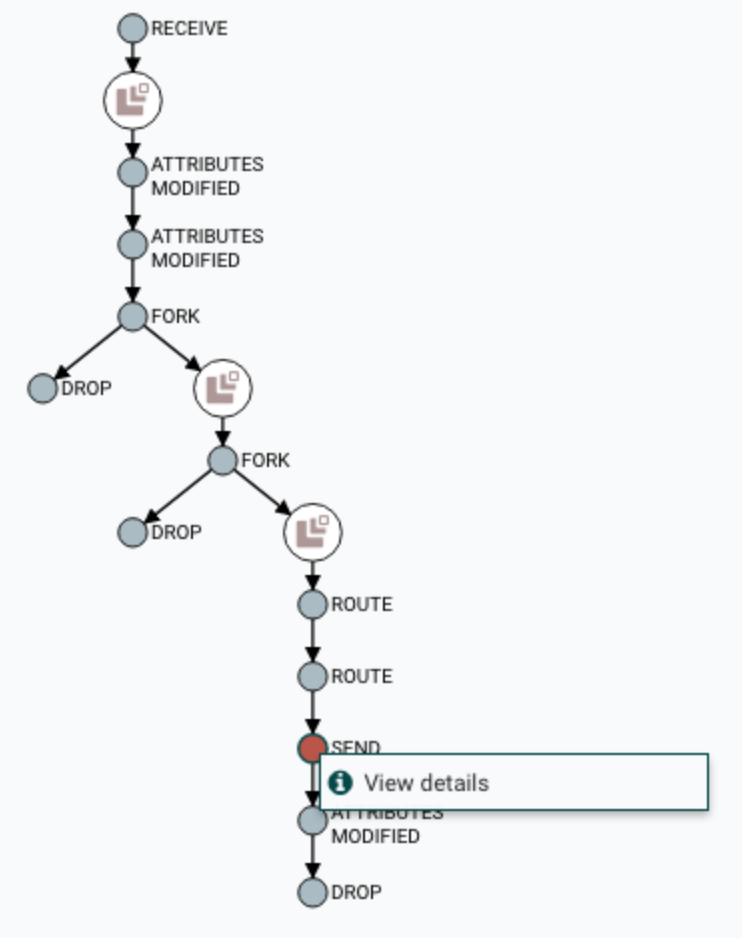

Users can explore the provenance chain (the directed graph representation of the provenance events) of any flowfile to review the path it followed through the data flow. This allows both broad and focused analysis of things like timing bottlenecks, system performance, and identifying critical paths. Sometimes open-ended exploration of this data will reveal or inspire potential improvements in the flow itself.

Replay

The provenance data is also crucial to a key feature of NiFi – allowing the user to replay flowfiles. As long as the provenance data has not been aged off and the referenced content is still available in the content repository, any flowfile can be replayed from any point in the flow. This greatly tightens the flow development lifecycle – rather than a “build and deploy” cycle, this encourages rapid refinement of a flow watching live (or slightly stale, but consistent) data proceed through different branches. A metaphor we use frequently in the NiFi community is that the data, much like water, is always flowing. NiFi is less about building permanent water pipes, and more like digging irrigation ditches from a constantly-flowing river.

While replay supports rapid flow refinement, the open secret is that it was developed for a different reason. NiFi connects many disparate systems, and in an enterprise environment, these are often owned and managed by different teams. Sometimes, data coming from System A, managed by Alice’s team, flows through a NiFi instance run by Norman, and then is routed to Bob’s System B. Saturday at 0300, an urgent alert comes into Norman saying that Bob hasn’t received data for the last 3 hours. A quick check of NiFi’s stats shows that Alice’s app is still producing messages on the correct Kafka topic and NiFi is consuming and delivering the data. After some troubleshooting, the RCA (root cause analysis) is that while the data was being written to a triage directory managed by Bob’s team, their application server was down, and the triage directory has aged out half of the delivered data.

In other loosely-coupled systems, the data may be lost forever. Not only does NiFi’s provenance allow Norman to prove that the data was delivered (important for the inevitable “blame game” that will be played by managers and budget people on Monday), but then to reconcile the “we’re all on the same team” mentality and help Bob out by replaying all the data that was lost back through the same flow.

“My CPU is a neural-net processor, a learning computer”

One of the buzzwords that you can’t go 20 minutes without hearing today is “machine learning” (that’s two words). While this means different things to different people (seriously, ask a data scientist sometime if you’re having trouble falling asleep), it’s generally accepted as “the computer learning something without being explicitly programmed”. Will Song has done some fascinating research on using NiFi provenance data for anomaly detection. Rather than examining the actual content of a flowfile (which can inhabit a broad, aschematic domain or be in a format that is not easily consumed or parsed), Will took the approach of examining the provenance metadata, which is tightly defined. By identifying anomalous data in timing, routing, etc., he could build a clustering model and predictor system.

The possibilities for NiFi are impressive – from early fault detection (think identifying timing increases to predict failing external hardware or network issues), to flow recommender systems (a Markov chain lookup of the most frequent follow-on processors when Processor X is added to the flow or configured with a certain collection of attributes), to flow recovery (self-healing flows that can intelligently re-route data when a specific destination is not available or bypass an expensive enrichment step when the flow volume increases above a threshold rather than delay downstream delivery).

Uphill Both Ways

The Provenance Repository was originally developed to provide a basic storage facility and sequential iteration. As noted by Mark Payne in NIFI-3356: Provide a newly refactored provenance repository

The Persistent Provenance Repository has been redesigned a few different times over several years. The original design for the repository was to provide storage of events and sequential iteration over those events via a Reporting Task. After that, we added the ability to compress the data so that it could be held longer. We then introduced the notion of indexing and searching via Lucene. We’ve since made several more modifications to try to boost performance.

At this point, however, the repository is still the bottleneck for many flows that handle large volumes of small FlowFiles. We need a new implementation that is based around the current goals for the repository and that can provide better throughput.

The PersistentProvenanceRepository served well for a long time, and while it is still the default implementation for a vanilla installation of NiFi, Mark did amazing work building a completely redesigned backing store called the WriteAheadProvenanceRepository.

Faster, Stronger, Better

The WriteAheadProvenanceRepository (or WAPR from here on out) uses a write-ahead log for the backing EventStore, rather than writing directly to journal files as the PersistentProvenanceRepository did. By combining the EventStore, which simply reports back an EventIdentifier to locate the written data, with an EventIndex (powered by Apache Lucene), the two components can work in conjunction to provide high throughput and efficient querying and retrieval.

Out of the box, WAPR is about 3x as fast as PPR, and this scales better as more disks and CPU resources are made available. In addition, with the Lucene EventIndex, event records are immediately available for query and retrieval, as opposed to the batch processing and ingesting done by PPR.

The WAPR implementation follows the classic Java design pattern philosophy “composition over inheritance”, so the underlying EventStore field belonging to the repository contains RecordWriter and RecordReader members. By providing a factory for each of these fields during EventStore construction, the store is responsible for instantiating these objects when necessary, but the repository itself can inject the relevant behavior through DI (Dependency Injection)/IoC (Inversion of Control). This is a crucial decision that made implementing the encrypted version much easier and cleaner.

Encrypt All The Things!

That’s 8500 characters to get to the point of this article – why and how do we encrypt the provenance repository?

The why is pretty straightforward – why not? In all seriousness, provenance data contains, in addition to generic timing and routing metadata, the value of the attributes at each point in the lineage. Many of these values can be quite sensitive. While NiFi has access controls for the REST API and UI, these details are written in plaintext (or compressed via GZIP) to the backing file system. While NiFi was originally designed with the expectation that it would run on managed hardware, many users are now requesting cloud deployments, or as I call it, “storing the crown jewels in someone else’s safe”. As part of an ongoing effort to harden NiFi for deployment on remote/”untrusted” hardware, we are continually looking for exposed surfaces. I have plans to provide an encrypted version of all three repositories (content and flowfile are the other two), and provenance seemed like the place to start, as it is the most ephemeral and the WAPR was most recently written and likely to be the cleanest, learning the most from the continual community feedback.

The how isn’t much more complicated. Because of Mark’s clean architecture, I was able to extend the WAPR and intercept the RecordReaderFactory and RecordWriterFactory that were injected into the EventStore constructor and simply replace those with my own implementations. This means the EncryptedWriteAheadProvenanceRepository file is a grand total of 159 lines (the unit test is 346).

The classes we will actually examine here are the KeyProvider interface and its two (current) implementations StaticKeyProvider and FileBasedKeyProvider, the ProvenanceEventEncryptor interface and its sole (current) implementation AESProvenanceEventEncryptor, and the new implementations of EncryptedSchemaRecordReader and EncryptedSchemaRecordWriter.

Vinz Clortho, Keymaster of Gozer

Providing access to encryption keys is one of the great challenges of data protection. Handling key material protection and availability, as well as key migration, rotation, and expiry are broad and complicated topics. For the initial implementation, I focused on two providers – StaticKeyProvider and FileBasedKeyProvider. The common interface is quite simple, providing four methods (Javadoc elided):

public interface KeyProvider {

SecretKey getKey(String keyId) throws KeyManagementException;

boolean keyExists(String keyId);

List getAvailableKeyIds();

boolean addKey(String keyId, SecretKey key) throws OperationNotSupportedException, KeyManagementException;

}

The methods are fairly self-documenting – by storing the keyId alongside the encrypted data, we are able to encrypt records with varying keys over time, reducing the risk of key compromise to be more granular.

The static implementation simply contains a HashMap of key IDs to SecretKey objects. It is initialized by reading the $NIFI_HOME/conf/nifi.properties file and reading the provided keys. These keys can be in plaintext or encrypted (along with any other sensitive configuration value) using the $ ./bin/encrypt-config.sh tool provided by the NiFi Toolkit.

if (StaticKeyProvider.class.getName().equals(implementationClassName)) {

// Get all the keys (map) from config

if (CryptoUtils.isValidKeyProvider(implementationClassName, config.getKeyProviderLocation(), config.getKeyId(), config.getEncryptionKeys())) {

Map formedKeys = config.getEncryptionKeys().entrySet().stream()

.collect(Collectors.toMap(

Map.Entry::getKey,

e -> {

try {

return CryptoUtils.formKeyFromHex(e.getValue());

} catch (KeyManagementException e1) {

// This should never happen because the hex has already been validated

logger.error("Encountered an error: ", e1);

return null;

}

}));

keyProvider = new StaticKeyProvider(formedKeys);

} else {

final String msg = "The StaticKeyProvider definition is not valid";

logger.error(msg);

throw new KeyManagementException(msg);

}

}

The file-based implementation expands on this by reading from a separate file (which can be located on a remote volume, etc.) and reading a key-value listing of key IDs and keys. The key material is Base64-encoded, encrypted and signed (using AES G/CM) hexadecimal representations.

Currently neither implementation supports the addKey method, but in the future, I expect a PKCS11-compatible HSM (Hardware Security Module) provider as well as bridges to sensitive value containers like Square’s KeyWhiz and Hashicorp’s Vault.

The KeyProvider interface and the implementations are also contained within the provenance package and module, but I expect to refactor them out to a framework-level service as part of changes in NIFI-3890: Create Key Management Controller Service.

Superfluous Interface Development

I’m kind of joking in the section title – the ProvenanceEventEncryptor interface has only four methods and only one implementation, but I wanted to ensure it could be cleanly extended in the future.

public interface ProvenanceEventEncryptor {

void initialize(KeyProvider keyProvider) throws KeyManagementException;

byte[] encrypt(byte[] plainRecord, String recordId, String keyId) throws EncryptionException;

byte[] decrypt(byte[] encryptedRecord, String recordId) throws EncryptionException;

String getNextKeyId() throws KeyManagementException;

}

Warning: Crypto nerd stuff ahead

The provided implementation uses AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) in G/CM (Galois/Counter Mode). AES is a symmetric encryption cipher, a variant of the Rijndael cipher, a substitution-permutation network, with a fixed block size of 128 bits and a key length of 128, 192, or 256 bits. This is in contrast to one of its most-common predecessors, DES (Data Encryption Standard), which used a Feistel network. If you want more detail than this, buy me a beer sometime and sit back. If you absolutely do not want more detail, consider yourself sane, and accept that it is sufficient for what we are covering here. In addition to the cipher selection, G/CM is an AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) mode of operation, which means that not only does it provide confidentiality (only people with the secret key can decrypt the cipher text), it also provides integrity (the cipher text cannot be undetectably modified by a party without the secret key). This is crucial for authenticity, especially in the application of provenance data, and common modes like ECB, CBC, and CTR do not provide this feature. An alternative construction would be to use a hash-based message authentication code (HMAC) like HMAC/SHA-256 or BLAKE2 with a separate key over the cipher text, but G/CM satisfies the requirements without a separate key and operation, so it’s a personal favorite for scenarios like this.

In the future, there may be ChaCha20-Poly1305 implementations for better performance, RSA or GPG implementations for asymmetric encryption using public-private key pairs, or even HSM implementations for encryption performed on remote/network-attached encryption appliances with completely contained keys.

Regardless, the actual interface contract is quite straightforward. The encrypt() and decrypt() methods accept arbitrary byte[] messages and some metadata, check that the specified key exists and is valid, and then perform the desired cryptographic operation (including serializing/deserializing the encryption metadata) and return the resulting byte[].

How to Lose a Super Bowl and Other Great Interceptions

We now turn to the pieces that actually make the repository work (everything up to this point has been pretty standard point-n’-click cryptography). The EncryptedSchemaRecordWriter and EncryptedSchemaRecordReader classes that we define will be wrappers extending and adding bonus functionality to the EventIdFirstSchemaRecord* classes. By providing different factories to the EventStore constructor as mentioned earlier, we’ll provide compatible instances which intercept the byte[] serialization/deserialization and also encrypt/decrypt the data. This means we don’t need any additional work to handle event indexing/querying, compression, etc. This saves us about 800 lines of repetition.

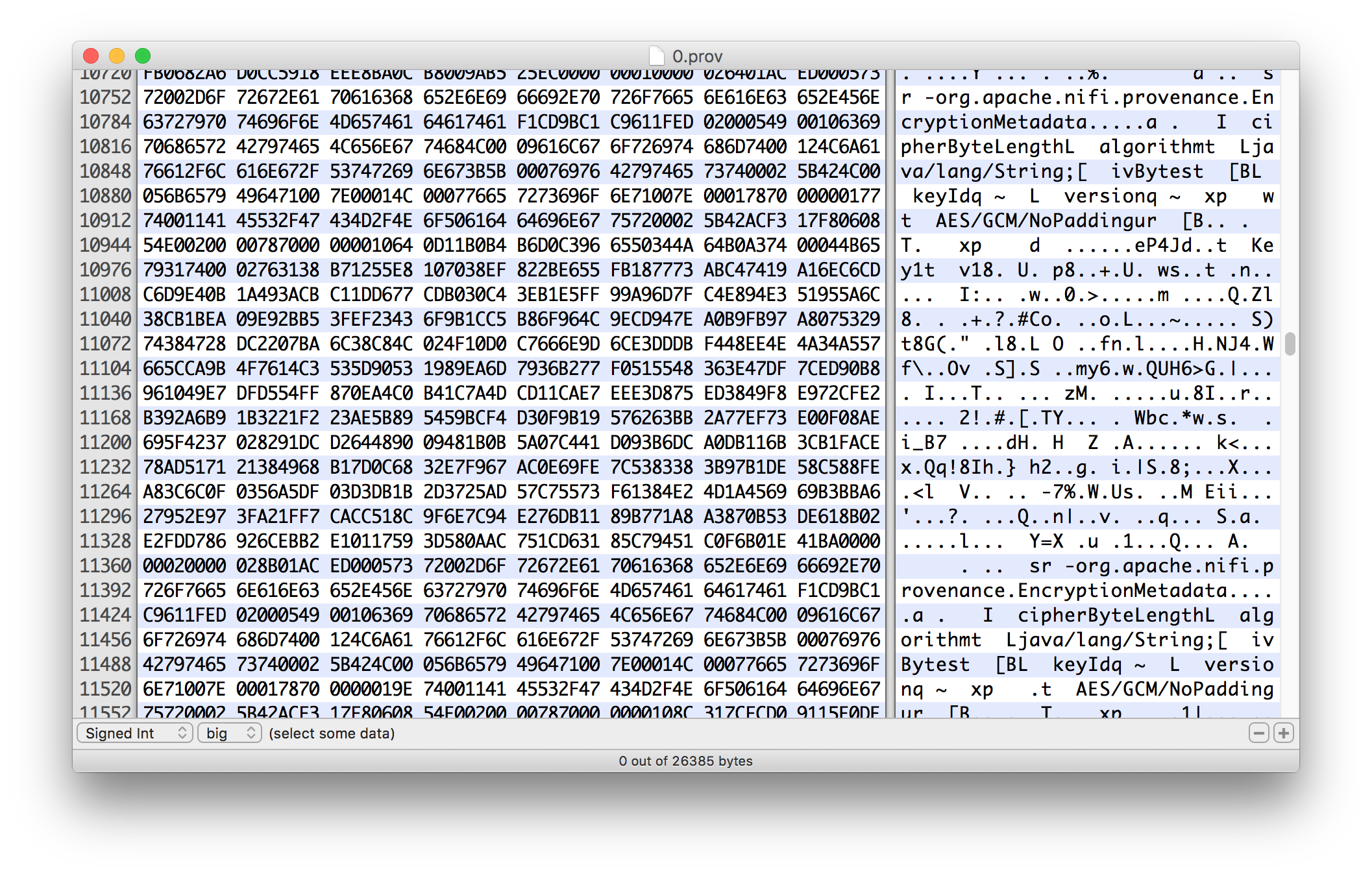

The encryption is easy – as stated above, the record is already serialized to a byte[] by the existing record writer, and that byte[] is handed to the ProvenanceEventEncryptor already described. The EncryptionMetadata (key ID, algorithm, IV, version, and cipher text length) is also serialized and prepended to allow on-demand retrieval and decryption (as a good crypto student, you did know we were going to use unique and non-predictable IVs for every event record, right?). This also allows records encrypted by two different keys to reside side-by-side in the repository with no ill effects.

The decryption operation is simply the inverse – retrieve the blob of data identified by the event ID (and read using random access via stored offset, not sequential reads) from the repository, retrieve the key and decrypt it, and then pass the plaintext serialized form to the delegated readRecord() method to be rehydrated into an object.

Configuring The App

As described in the Apache NiFi User Guide and Apache NiFi Admin Guide (light reading for insomniacs), the encrypted provenance repository does need a little bit of configuration in nifi.properties. Every property is verbosely described on that page, but here is the simplest valid configuration:

nifi.provenance.repository.implementation=org.apache.nifi.provenance.EncryptedWriteAheadProvenanceRepository

nifi.provenance.repository.debug.frequency=100

nifi.provenance.repository.encryption.key.provider.implementation=org.apache.nifi.provenance.StaticKeyProvider

nifi.provenance.repository.encryption.key.provider.location=

nifi.provenance.repository.encryption.key.id=Key1

nifi.provenance.repository.encryption.key=0123456789ABCDEFFEDCBA98765432100123456789ABCDEFFEDCBA9876543210

Does It Actually Work?

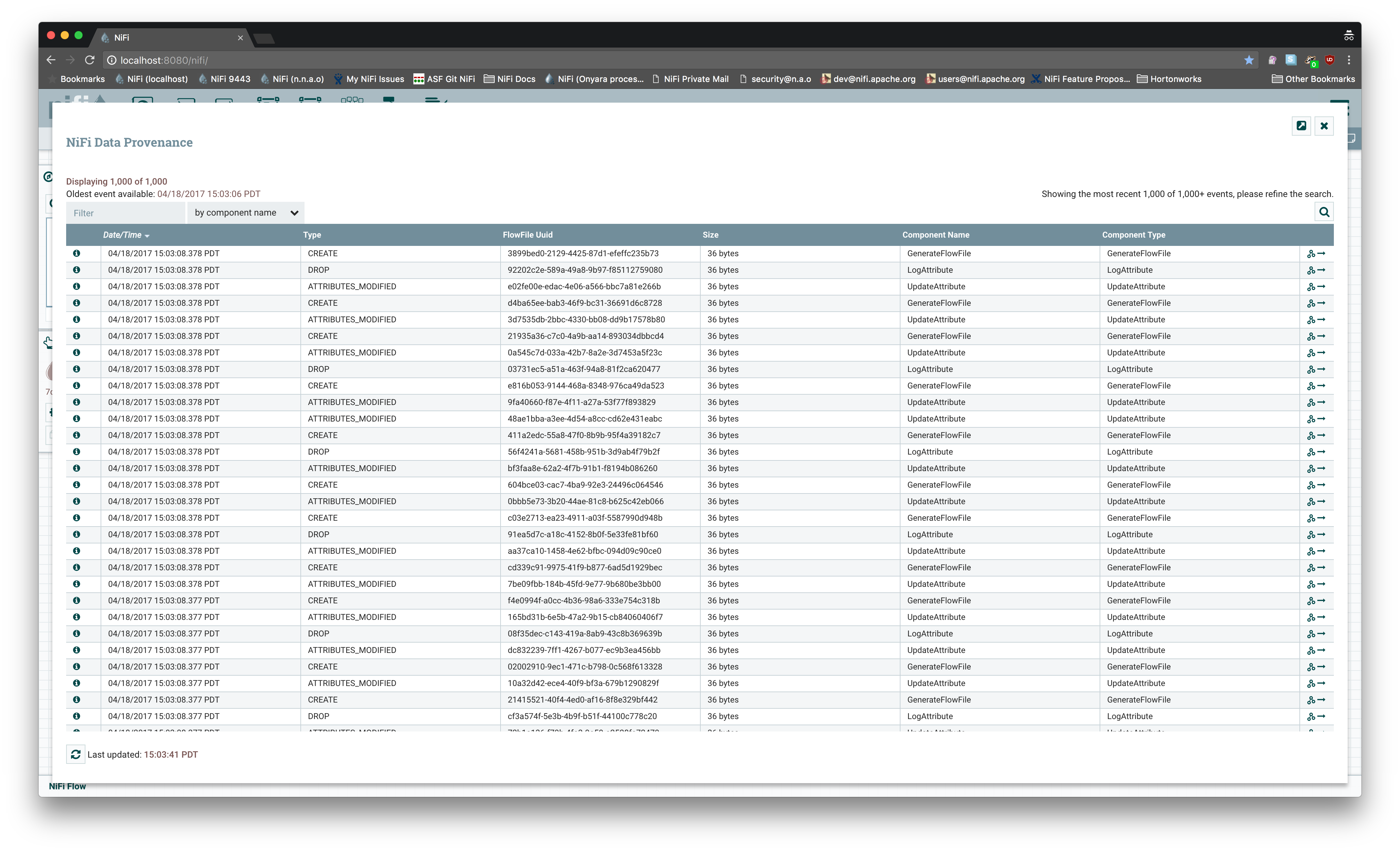

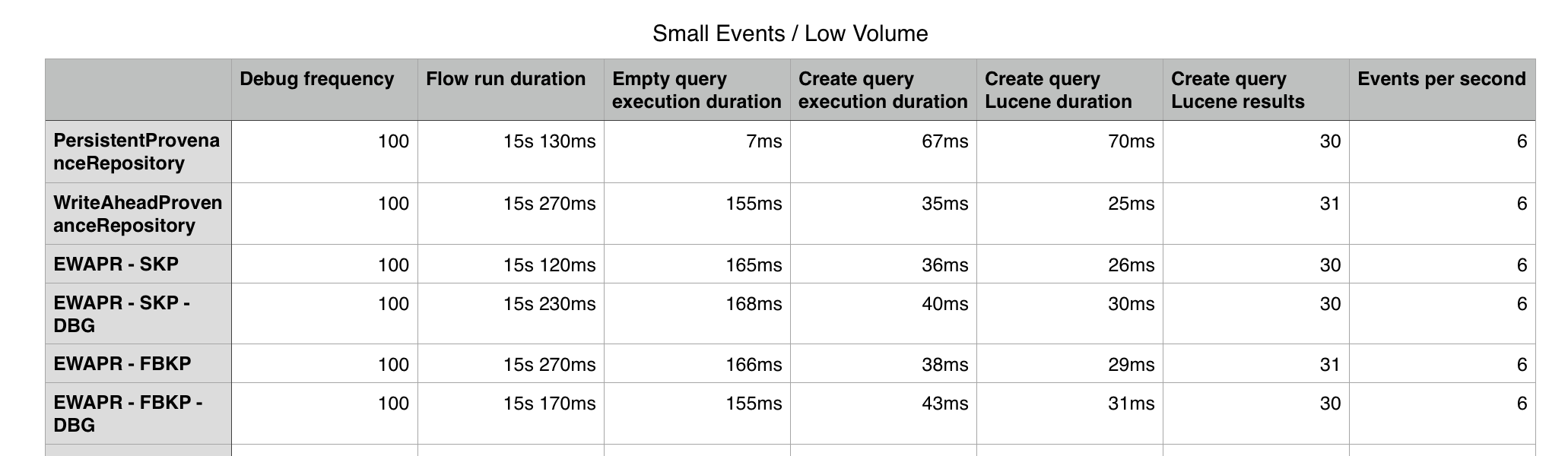

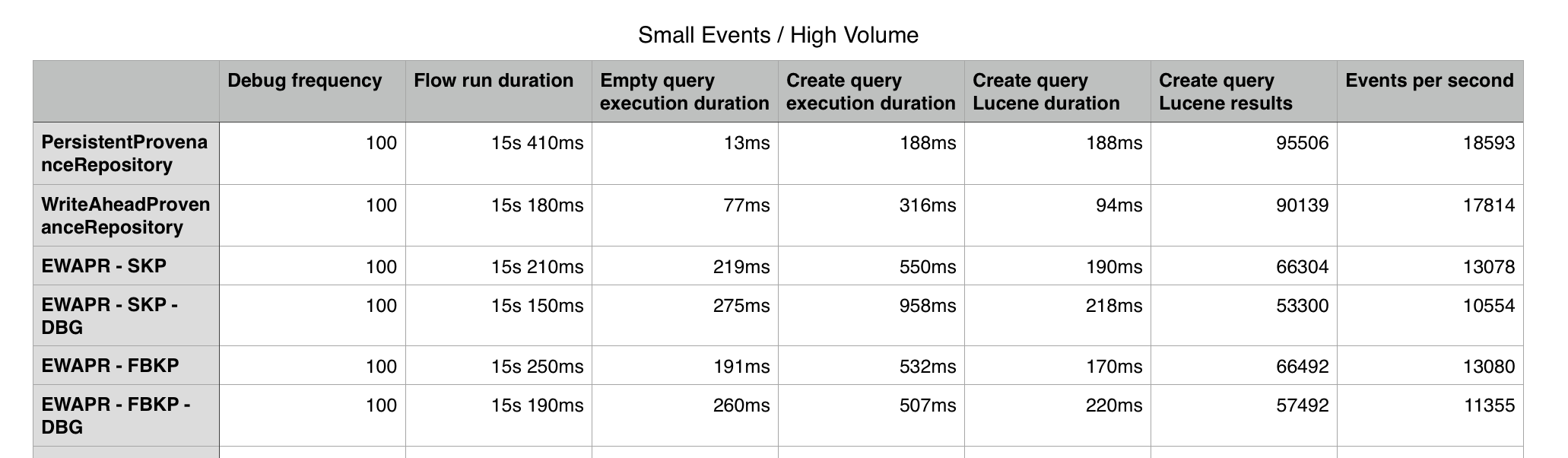

Encryption always adds costs to any software. I ran some basic performance tests to provide some metrics in PR 1686, and I found that with low flow volume, using an encrypted provenance repository was more than twice as fast as the old PPR and almost identical to the new WAPR. This led me to double-take and question “is it actually encrypting anything?”

I used my handy Hex Fiend to examine the actual files on disk to ensure the data was being encrypted. Here you can see the EncryptionMetadata being serialized via Java serialization and the cipher text of the event record following.

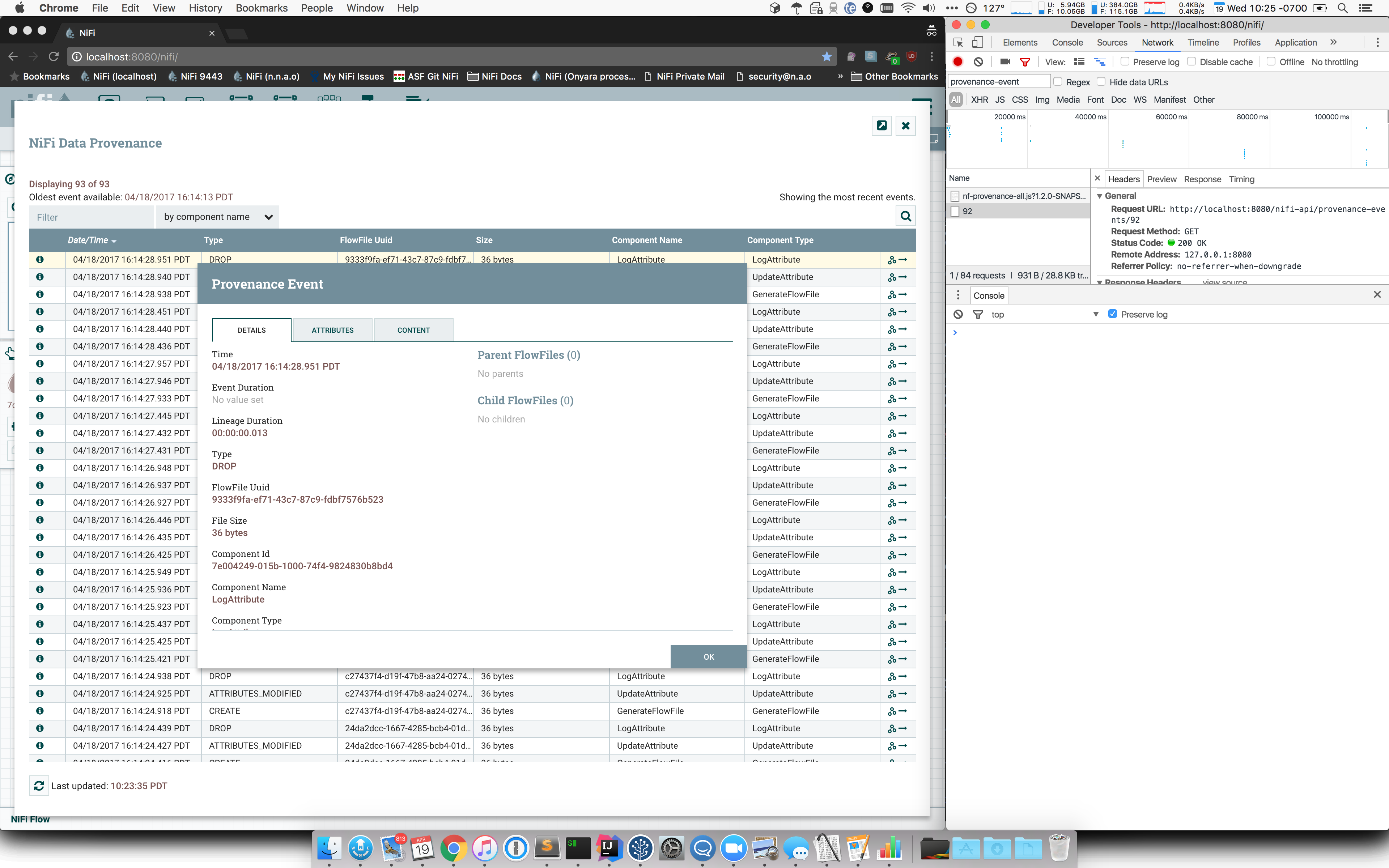

Ok, so once the data is encrypted, is it still useful in the app? Sure enough, a provenance query returns perfectly human-readable records through the REST API and the UI.

With high flow volume, I did “luckily” see more performance cost. Still, running with an encrypted provenance repository, the flow could handle about 13k events per second. While the flow performance was slower than the original PPR, the provenance queries were almost identical (and sometimes even faster).

Long story short, if you like writing encrypted provenance data to your disk, NiFi’s got you covered.

Back to the Future

There is still plenty of work to do here. Repository implementation migration is not as smooth as it could be, tools for migration and key rotation would be nice, the KeyProvider and other services can be extracted to the framework level, content and flowfile repository implementations are still necessary, and provenance records themselves do not have cryptographic signatures over their content (for chain of custody, governance, and integrity guarantees). The User Guide has a section devoted just to “Potential Issues” involved. As provenance data isn’t intended to be stored long term in NiFi, but offloaded to a glacial store like Apache Atlas, these aren’t priority issues. I would recommend you try the encrypted provenance repository on non-business-critical data at first, but in our tests, it has been pretty stable.